Why Media Activism?

1. Uncertain Times: Divide and Rule

It is probably not a coincidence that social media has been experiencing such upheaval and disruption at a time when the planet itself is in crisis. What was once taken for granted by many of us – even in more privileged sections of the world – is suddenly being questioned.

More and more of us no longer approach our week in the comfortable assumption that our income opportunities will continue to exist, that our travel destination dreams almost anywhere around the globe will be realised, or that the rights of marginalised groups will inevitably improve as part of our “progress.”

Yes, we are living in the “Roaring Twenties”: a time of moral panic, pandemic, climate chaos, and the threat of nuclear war between nation states. A time of uncertainty.

It didn’t have to be this way. There are enough materials on our planet to provide housing, clothing, and food for all people, all around the world, so that everyone can live a dignified life. Many of us are questioning why this isn’t already a reality: why don’t we have a system where society functions fairly and sustainably – from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs?

"The restricted movement of bodies across borders is parodied by the free flow of cash around the world. The ideas of autonomy and mutual aid can help us rethink our places in the world as interlinked groups who can mutually support one another." Shuli Branson, Practical Anarchism.

The system almost all of us are subjected to in the world is one where a forest only has value if it’s cut down, where buildings sit empty while communities are in need – a system where profit has the utmost importance over all other things; a system that actually denies care and prevents progress if it doesn’t mean profit; a system of greed and growth; a system of supposedly endless extraction of natural resources…which is, of course, incompatible with our existence on this planet.

"We'll go down in history as the first society that wouldn't save itself because it wasn't cost-effective." – Kurt Vonnegut, University of Oregon speech, 1990

But this system – capitalism – attempts to justify itself with the principle of hierarchy: placing the interests of one entity over another not only serves to attempt to excuse this hierarchy of profits over the natural world, but also conveniently divides our society that is also subjected to these hierarchies – rich over poor; famous over obscure; white people over Black, Indigenous, and people of colour; straight people over queer folks; men over women; cisgender over transgender, non-binary, genderqueer, genderfluid and gender non-conforming folks; non-disabled over disabled people; human over non-human animal, and so forth. This is why any successful anti-capitalist movement must grasp this intersectionality.

"The thing about hierarchy is, as a minority, or 'lesser,' you can never ascend to the peak but you can push others down beneath you." - unknown

Societies remain in turmoil, ripped apart by these differences, in-fighting, when the system has actually been quite clear in its division – hidden in plain sight before us all – for a few hundred years now: the distinction between those who own and control property and business, and those who do not; the owning class and the working class. The ultimate division – fuelled for years by white colonialism.

"The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organise as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth." - from the preamble to the IWW constitution

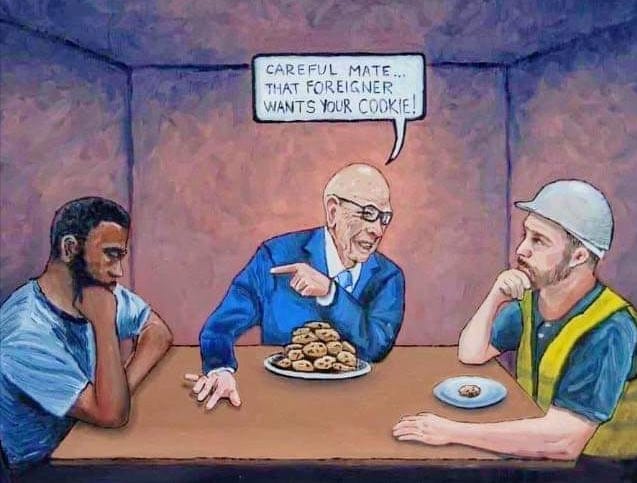

We are told we must "earn" a "living." For many of us, the best part of the day is lost to work. While the labour of workers has long made money for businesses, despite that labour itself generating the value of the products and services being sold, the workers have usually only ever received a small cut of the profits – profits that are in fact, then, unpaid wages, used instead to increase wealth for the capitalist class: the greatest hierarchy of all that is inherent to the system; essentially hard-coded into it. Capitalists often boast about "earning" a million dollars, apparently all through their own hard work. But through the very principle of ownership, a capitalist cannot possibly make a million, only take a million. Still, those unwise to the injustices of this are instead easily distracted by other aforementioned hierarchies manufactured for society to fight over amongst themselves, while the rich get richer, and people suffer in various kinds of poverty – not just material poverty, but other kinds of poverty, too, such as poverty of education, and poverty of leisure, poverty of hope…which helps the system to continue.

“How in the hell could a man enjoy being awakened at 8:30 a.m. by an alarm clock, leap out of bed, dress, force-feed, shit, piss, brush teeth and hair, and fight traffic to get to a place where essentially you made lots of money for somebody else and were asked to be grateful for the opportunity to do so?” - Charles Bukowski

Of course, this system is completely unsustainable. Expansion of profits and narrow-minded never-ending extraction means destruction of the planet itself. The capitalist class seem confident they can close themselves off from the effects while the working classes continue to fight amongst themselves outside. But inherently, humans are social creatures and enjoy spending time with others they have shared experiences with, yet climate change, wars, famines, discrimination, financial uncertainty and other conditions lead to displacement; in turn, nation states open and close borders to control the flow of people as it suits them and their economic motives at the time – essentially also opening and closing access to everyday essential resources that, as mentioned, are plentiful enough to easily meet the needs of all human life on earth, yet are instead ring-fenced and hoarded by a greedy capitalist class, enabled by nation states that serve these immensely powerful interests. And this is why we are now seeing late-stage capitalism requiring greater, more ruthless authority, as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. It’s why capitalist interests always have a tendency to accept fascism, propaganda, and disinformation as a way to keep the same old system on track when society experiences unrest.

"I have no country to fight for; my country is the earth, and I am a citizen of the world." - Eugene V. Debs

So often, so many of us resign to an apathetic view that the world is how it must be, our vision of an alternative future obscured by the current culture and its media. After all, that neoliberal icon herself, Margaret Thatcher, proclaimed that “There Is No Alternative” while working closely with media moguls such as Rupert Murdoch to perpetuate this narrative, manufacture consent, and develop distractions and divisions amongst the working classes.

"The assumption that what currently exists must necessarily exist is the acid that corrodes all visionary thinking." - Murray Bookchin

The media lies in the hands of very exclusive interests: for example, in the United Kingdom alone, just 3 companies dominate at least 80% of the British newspaper market – Reach, Rupert Murdoch’s News UK, and the Rothermeres’ Daily Mail Group, the latter two of which have, historically, been notoriously right-wing (though none are, by any stretch, even remotely left-wing in any way, shape, or form); Thatcher’s old friend Murdoch was an ardent supporter of Bush, Blair, and the invasion of Iraq, for example, while the Rothermere family had their newspapers back the British Union of Fascists in the 1930s, and their editorial narrative hasn’t shifted much at all since. And it isn’t just the private companies in control of much of the media that have retained a right-wing stance: contrary to popular myth, the BBC are inherently anti-left – not, perhaps, despite being a state broadcaster but because they’re a state broadcaster. While Russia Today, or RT, are roundly (and rightly) criticised for being a state media group and therefore at the behest of the Russian government, the BBC, too, is controlled by the increasingly right-wing, authoritarian U.K. government – but repackaged as, instead, a “public” broadcaster. Ultimately, government-controlled media can no more reflect the views or interests of the public than professional politicians can.

"What this country needs is more unemployed politicians." - Angela Davis

There’s an old saying that politicians piss on us and the media tells us it’s raining. This is because the establishment media that lies behind most of our sources of information are comprised of massive hierarchical institutions of centralised power where even well-intentioned journalists are often reliant on retaining relationships with influential establishment contacts for access to inside information or halls of power, or simply target-driven in their jobs therefore reduced to copy-and-paste from corporate press releases, or even entire re-writes or rejections from editors and “higher-ups” who are close with – or even perhaps one of – the elites in charge.

"I entirely respect the radical leftists who refuse to speak to mainstream publications. Venues like CNN have institutional interests in presenting far-left protesters in their vile 'both sides' narratives, drawing false equivalences with the far right, and there’s every reason to refuse to participate in that." - Natasha Lennard

A media tutor once said, “If someone says it’s raining and another person says it’s dry, it’s not your job to quote them both. Your job is to look out the fucking window and find out which is true.” In this culture of the modern newsroom, even if there was any inclination to look out of that proverbial window, that’s too often too much effort, as pressures from bosses reduce journalists to, at worst, remaining totally disconnected from marginalised communities, and at best, “reporting” while giving equal say to both perpetrator and victim, apartheid regime and refugee, corporation and community, all in the name of “unbiased” reporting.

"If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor." - Desmond Tutu

It is unreasonable to attempt to give equal say to unequal parties when one of them already dominates cultural narratives. Media is actually supposed to be biased – in favour of the oppressed. It has to be about publishing content that the powerful do not want to be published. Otherwise, it simply exists to constantly reinforce power imbalances. To paraphrase Finley Peter Dunne, the job of the newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Establishment media has completely failed to do this because of its hierarchical elitist institutions and class-exclusive professions. Its entire culture is at odds with the interests of our communities. And so, it’s up to us. It’s always been up to us. Many of us already realised that.

2. System Fail: The Millennium Bug, Coronavirus, and Conspiracy Theories

The 21st century began, in many ways, in fitting fashion – as a harbinger of things yet to come. The fear and panic around the Y2K bug produced vast amounts of confusion and conspiracy theories that would come to pollute our online spaces with increasing frequency.

And yet it had started out so promising: with the web offering an unprecedented method of sharing information and ideas that had lacked coverage in the pages of newspapers and the bulletins of television news. Initially, this was often found in the weblogs (or "blogs") that provided a platform for voices rarely heard up to this point. “The web dramatically alters the balance between multinational and activist media,” declared an opening statement of the first Independent Media (or Indymedia) Center. “With just a bit of coding and some cheap equipment, we can set up a live automated website that rivals the corporates’.”

Under the slogan “Don’t hate the media – become the media,” a network of Indymedia Centers spawned out of the WTO protests in 1999 and quickly expanded world-wide with global opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, as activists reported on actions in mere minutes, complete with photos and videos, often offering different perspectives on protests against the G8 and the G20 to those narratives provided in the papers or on TV. Sadly, it didn't last.

"As the anti-globalisation movement from which it had emerged started to ebb away...Indymedia went into free fall. The open publishing nature which had allowed anybody to take part, write up action reports and publicise events, proved also to be its weakness as conspiracy theorists and anti-Semites began posting whatever they liked. It was partly in reaction to these drawbacks that we launched what eventually became libcom.org." - libcom.org

In addition to Indymedia’s lack of a coherent, comprehensive system of democratic editorial oversight, the "blogosphere" was at the same time being somewhat superseded by the emergence of social media sites that co-opted such features of content creation and media uploads alongside messaging and profile-building. And profiles were increased in every sense: commentators catapulted careers from their large followings on social media, and in some cases launched their own websites, taking advantage of the loss of faith in establishment media.

Under the guise of offering “alternative” media, a wave of websites overwhelmed us within just a few years, leaving us with a disorientating flood of sites such as The Young Turks, MintPress News, Redfish, and The Grayzone building a reputation for fiercely “anti-imperialist” reporting – only for such coverage to be largely restricted to critiques of Western imperialism, with funds from Russian powers supporting these narratives that undermine Western superiority while platforming white supremacists and far-right conspiracy theorists. The existence of anything questioning Western imperialism, at face value, can seem appealing to many of us, and these outlets are often designed to exploit such sentiments while being at best big state socialists, or at worst disinformation channels serving the interests of the powerful Russian government, often platforming bigots and pseudoscience personalities. But across the web, they’re all fighting for clicks, whether they be Bellingcat exposing The Grayzone as state stooges, or The Grayzone attempting to return fire by making the same claim back at them. Regardless of the influences or agendas, they’re all compromised and open to these criticisms (though some worse than others, of course). And, in order to raise and retain their profile, they’ve all been largely dependent upon traffic from pages on social media sites.

While MySpace’s purchase by Rupert Murdoch was ill-fated, it was not because social media was contracting in any way, but because it was in fact expanding: as the emerging sites suddenly rivaling MySpace attracted users in droves, what remained of the Indymedia network began to largely collapse. Facebook and Twitter were utilised for both the Arab Spring, and then the Occupy movement, which rose up after the 2008 global financial crisis. Large banks were bailed out; large swathes of populations were subjected to harsh austerity measures. The system remained in place – essentially, it turned out, aided and abetted by the same social media sites that were supposedly useful in challenging that system.

The development of the world wide web stoked our naive expectations of a more free exchange of ideas in an online commons that was, under capitalism, quickly seized and bought up by virtual landowners. But few phenomena offer a better example of this than social media centralised, owned, and controlled by corporations.

As new media replaced old media for advertising opportunities, companies were wooed by promises of a budding target market, one all too willing to engage with brands. It became a largely accepted model: online spaces with millions – even billions – of users, all providing their data. In turn, this was sold to advertisers, creating huge profits for private social media companies. User data provided a wealth of information through profiles, polls and social graphs. Tools emerged to gauge favourite foods and films, or places a person frequented – even private matters such as sexuality and personal anxieties became figures in datasets.

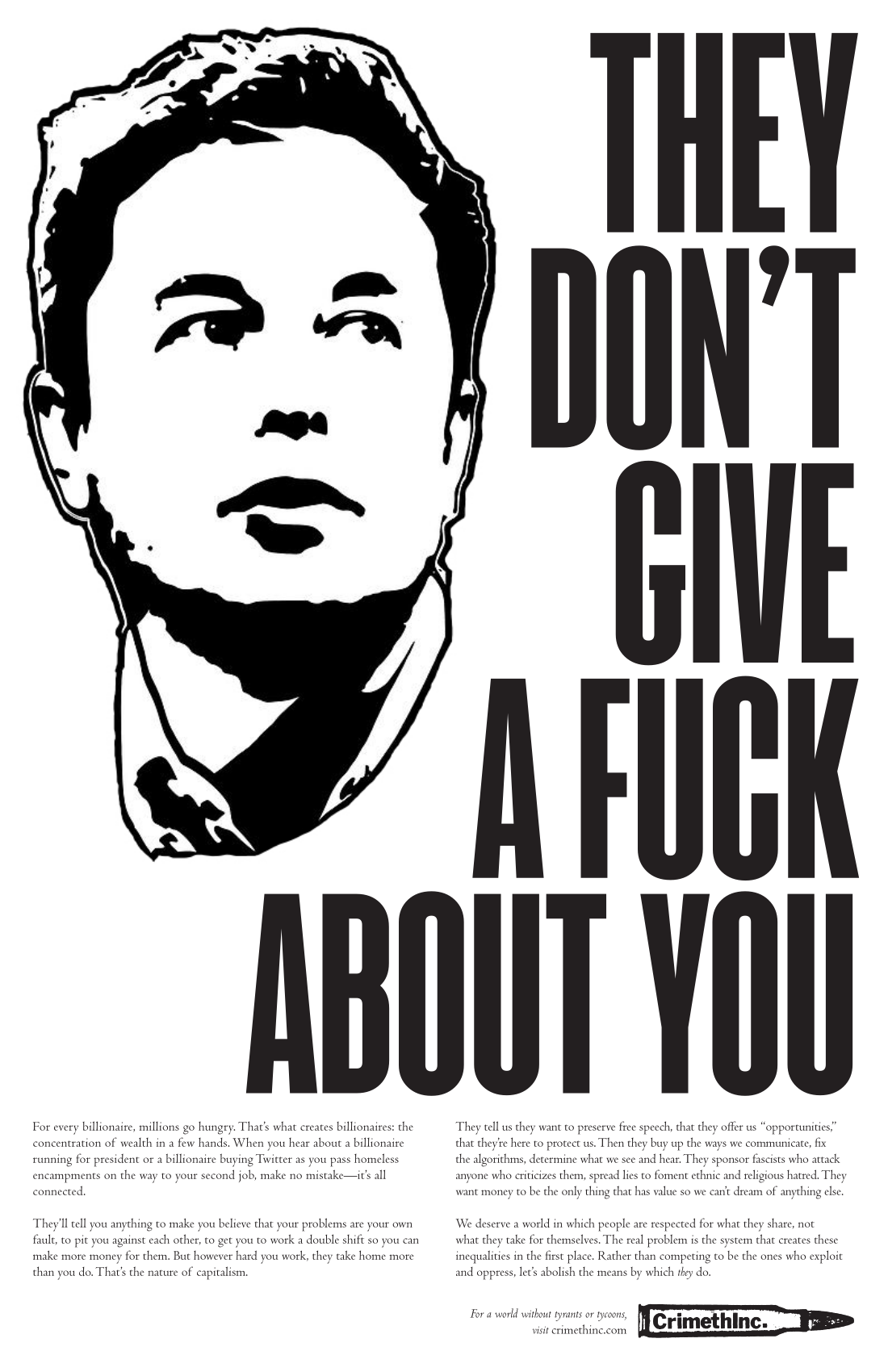

Far from being platforms in proverbial “town squares”, as they were often lovingly referred to, these social media sites – aside from making money from selling user data to advertisers – are privately-controlled entities subjected to the whims of billionaire owners and their desire to protect the capitalist class, including by enabling the spread of misinformation.

In the run-up to the U.K. general election in 2019, a staggering 88% of Conservative Party posts on Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook were “misleading.” (Facebook did ban one of their ads, but only because it infringed the BBC’s intellectual property rights.) More recently, Covid denialism (linked heavily to the far right and nicely serving capitalist ideology) has been permitted to thrive via conspiracy theories thrown around on Facebook as well.

Yes, conspiracy theories, misinformation and misleading campaigns thrived more than ever before. Even social democratic challenges to “business as usual” such as Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn were soon stamped out.

“Politics hates a vacuum. If it isn’t filled with hope, someone will fill it with fear.” - Naomi Klein

In countries from the U.K. and U.S. to Russia, the prevention, decimation, and eventual disappearance of even these wildly popular yet remarkably mild alternatives and tweaks to the system led populations of angry, confused, voters remaining an electorate to become seduced by something else, something different, that promised them a much-wanted drastic shake-up: a form of fascism openly promoted, for years, by a media that meanwhile engaged in an all-out assault on all things not conservative or neoliberal. This fully unleashed plague of fascism grew and spread to Brazil, Argentina, Italy, the Netherlands, and all around the world. Nowhere has been safe from these toxic elements of capitalism’s cocktail of authoritarianism utilised in an attempt to justify its principles of power, profits, and endless exploitation and extraction of planetary resources as we approach the brink of destruction. People are faced with not just worldwide inequality, but also an ongoing global pandemic and climate crisis. All the while, the capitalist system remains supposedly sacrosanct.

Then came Elon Musk. Twitter was far from perfect even before he bought it – founded by Noah Glass, Evan Williams, and Biz Stone, with Jack Dorsey as CEO, it was designed to be a private entity which inevitably turned its attention towards generating revenue. When Musk purchased the service, he claimed to be a “free speech absolutist” at the same time as overseeing bans on anti-fascist accounts such as Crimethinc at the behest of the far-right voices he adheres to and even amplifies online. With capitalism accelerating global crises, and many now rejecting traditional electoral systems as realistic solutions, Crimethinc is one of several similar accounts that obviously threaten billionaires such as Musk – personally, politically, and practically: they make him feel threatened because they are anarchistic. And not because anarchism is, in fact, something sinister. Not for us, it turns out, anyway.

“Chances are you have already heard something about who anarchists are and what they are supposed to believe. Chances are almost everything you have heard is nonsense. Many people seem to think that anarchists are proponents of violence, chaos, and destruction, that they are against all forms of order and organisation, or that they are crazed nihilists who just want to blow everything up. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Anarchists are simply people who believe human beings are capable of behaving in a reasonable fashion without having to be forced to. It is really a very simple notion. But it’s one that the rich and powerful have always found extremely dangerous.” – David Graeber

3. Antidote: Why Capitalists Fear Anarchism

The continuing crises caused by capitalism leave ordinary people feeling powerless in the face of powerful interests when, instead, communities could be organised by and for the people who live in them. This may seem obvious to us, but such a system of direct democracy would threaten those concentrations of power protected by the nation state, with its “representative” democracy of careerist professional politicians claiming to solely speak for thousands or even millions of people until the next ballot box election cycle where we choose between one suit or another, red or blue, like Coke and Pepsi; both options bad for us.

“Power corrupts and those who spend their entire lives seeking power are the very last people who should have it.” – David Graeber

Ultimately, the state is another concentration of powerful interests, with its hierarchy of institutions, armed forces, policing over its people, and often punitive welfare systems where, while elites hoard their immense wealth, people scramble for scraps of assistance to experience a life less miserable – assistance that can be withdrawn at the whims of a government whose politicians swap, switch, and change positions, portfolios, and policies in the corridors of power; policies that can remove support for swathes of people with the mere flick of a pen; no sword even needed to commit this kind of violence. And that’s exactly what it is.

"Read and learn. You'll see how many ways there are to kill." - Libertarias

We all tend to agree that refusing to help place food within reach of the needy when we have the chance is still a form of starvation through cruelty of inaction. It causes easily avoidable harm. So these policies are state violence. And there is a term for the perpetrators: desk murderers. These people in power already killed many people, all without ever having to dirty their hands. Austerity continues, yet if the needy take food from a market without paying for it, the state ensures that they are arrested, prosecuted, and punished.

"The greatest crimes in the world are not committed by people breaking the rules but by people following the rules. It’s people who follow orders that drop bombs and massacre villages." - from Wall and Piece by Banksy

The hierarchy of the state means power is concentrated at the top of a centralised system, comprised of people achieving such power usually by having worked with others in powerful positions – perhaps their predecessors, maybe other hierarchical institutions including city councils, cops, or the military. In countries where the state embraces corporatism, many politicians are lobbied or even financed by corporate interests, and even if they happen to have introduced laws to supposedly stop corporate abuse, these big companies can get away with it through a form of legalised bribery known as government fines.

Even the few anti-capitalist politicians with seemingly good intentions have always historically found themselves at the mercy of powerful interests domestically and/or globally – if not sabotaged or smeared by agents of capitalism, then certainly seduced or trapped by the power of the state; compromised or even corrupted. No surprise, then, that not one has ever succeeded through our entire history. And no government has ever liberated all of its people from oppression – perhaps because centralised power is oppression.

"Our present economic system is more likely to reward people for selfish and unscrupulous behaviour than for being decent, caring human beings. ...Most people don’t think there’s anything that can be done about it, or anyway — and this is what the faithful servants of the powerful are always most likely to insist — anything that won’t end up making things even worse. But what if that weren’t true? And is there really any reason to believe this? When you can actually test them, most of the usual predictions about what would happen without states or capitalism turn out to be entirely untrue. For thousands of years people lived without governments. In many parts of the world people live outside of the control of governments today. They do not all kill each other. Mostly they just get on about their lives the same as anyone else would." – David Graeber

"By virtually any standard – geographic, economic, cultural, technological – the modern State has been more successful than any previous system at imposing itself on humanity and the earth," explained Eric Laursen in the book The Operating System. "Over five centuries, it has harnessed capital, labour, science and technology, and firepower to remake almost the entire world through conquest, slavery, innovation, economic exploitation, the subjugation or evisceration of societies that followed other models, the systematic stripping of the planet's natural resources, and the inculcation of its worldview into every one of us." He continued: "These were not by-products or unintended consequences. They also didn't have to happen. But these practices were integral to the State's goals and ambitions; they are part of its DNA. In the past century, the atrocities have grown in magnitude as the State has grown more powerful: over six million killed in Nazi Germany's death factories, millions imprisoned and dead in the forced labour camps of the Soviet Union and Maoist China, and an unprecedented incarceration boom in the United States that's created a powerful new private industry of prisons and detention centres."

History has judged the state and the verdict is damning indeed. When we think of Joseph Stalin or Adolf Hitler, or even Donald Trump, we know that their incredible power, oppressive might – and atrocities – were only ever possible because of something we have quite remarkably been conditioned to take for granted: the state. It's time to recognise and utilise a different way of organising societies in a fair and sustainable way. Our very survival depends on it, because little time remains. The next promising politician making promises that can never be realised through the state essentially threatens that survival by diverting, and absorbing, our limited energies into long voting drives where we're offered "the lesser of evils" at worst and, at best, a single seemingly well-intended politician who is destined for failure – like all others before them. It's the same thing, over and over again, while irrationally expecting different results.

"The long project of the state and capitalism has been to make people dependent on their institutions for basic necessities instead of determining their lives for themselves. So in a way, the shape of our lives 'needs' the state – but we don't get to determine that shape or prioritise other needs. In other words, the state causes the problem and then purports to fix it – while always decreasing the actual resources it gives us. We should take all we can from the state, no question; but we must also imagine ways of living that don't depend on an external centralised authority imposing its structure on us to keep us orderly and complacent." - Shuli Branson, Practical Anarchism

While people for years have argued with one another about political parties across the spectrum, it turns out that the biggest problem wasn’t to be found on a horizontal line of “left” or “right” politicians in the halls of power, but at the top of a vertical line – of those holding power over the working class “subjects” or “citizens” beneath them. Yes: the problem was a concentration of power itself. A line must never be vertical, and only be horizontal when it’s endlessly representing all people, essentially joined in a circle.

"Most of us have little experience in groups where everyone gets to make decisions together, because our schools, homes, workplaces, congregations, and other groups are mostly run as hierarchies. Our society runs on coercion. You have to work or go to school and follow rules and laws that you had no say in creating, whether you believe in them or not, or risk exclusion, stigma, starvation, or punishment. We do not get to consent to the conditions we live under. Bosses, corporations, and government officials make decisions that impoverish most people, pollute our planet, concentrate wealth, and start wars. We are only practiced at being allowed to make decisions as individual consumers, and rarely get practice making truly collective decisions. We are told we live in a system of 'majority rule,' yet there is rarely anyone to vote for who is not owned by – or part of – the 1 percent, and the decisions those leaders make do not benefit the majority of people." - Dean Spade

Direct democracy – and not state socialism, which has, throughout history, given us aggressive power blocs and forced labour camps – is true socialism, where people literally decide for themselves on how their communities are organised. It is often called libertarian socialism…or simply anarchism: yes, a scary-sounding term for the establishment media, maybe, but in fact the word “anarchism” derives from the ancient Greek word anarchia, which basically means “without leader” or “without authority.” No lines, only circles.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon once stated that “anarchy is order without power,” a phrase that many understandably assumed to have inspired the symbol of the letter “A” inside a circle. After all – as history has already shown in such a short time – capitalism brings us terror, corruption, and complete chaos, so despite what its defenders claim about anarchy, it is anarchism that offers us order and freedom from tyranny at long last: in fact, a world without leaders, states, or borders; a world opposed to hierarchical structures; a world with “work” and finance replaced by simple acts of communal care; a world in which individuals can collaborate together to create and control their own collective organisations federated and democratically coordinated (rather than competing) with one another; a world where communities act locally but think globally; a world without desperation, crime, police, prisons, or powerful institutions, and where people’s needs are met through the principle of mutual aid, alongside community support systems, conflict resolution, restorative and transformative justice…and direct democracy.

This is why anarchism has long been referred to as “the Beautiful Idea.”

"Unlike representative government, consensus decision-making lets us have a say in things that matter to us directly, instead of electing someone who may or may not advocate on our behalf. Consensus decision-making is a radical practice for building a new world not based on domination or coercion." - Dean Spade

Such concepts are, of course, fundamentally based on inclusion, care, and non-violence and yet, as innocuous as all that may seem, those of us who promote them and participate in them are often targeted and demonised by the state – so incredibly threatened states are by such programmes’ potential to de-legitimise, undermine, and even replace the state itself. It’s why the rise of fascistic right-wing violence is generally greatly ignored. It’s why, instead, peaceful campaigners can be called “domestic extremists,” cute bookstores can be considered “hotbeds for terror plots,” an activist can be imprisoned simply for attending an “anti-state dinner,” an urban farm can be raided for “conspiring” to provide compost toilets and a wheelchair track to a peaceful climate camp, and it’s why the free breakfasts provided by the Black Panthers were considered a “security threat.” As Shuli Branson pointed out in the book Practical Anarchism: “The state will object to even simple kindness or humane treatment if it isn't concentrated through its own power.”

“The only people who are actually afraid of these collective ways of organising are the politicians, cops, and corporations who seek to preserve their absolute power over humanity. If we had ways of living more collectively, satisfied our needs through mutual aid, and had solidarity with each other, people may realise they don’t need the state or capitalism, and they may realise that the greatest causes of human suffering and barriers to freedom and security are the state and capitalism.” - statement from 12 of the 61 people indicted on RICO charges in Atlanta

There is hardly any wonder Elon Musk, his capitalist class, careerist politicians and presidential candidates are so deeply offended by such harmonious, horizontal ways of organising society: these ways mean less power for such interests, and instead ordinary people doing things and deciding for themselves, rendering the current system of hierarchy completely exposed, and ultimately useless.

For now, the current system means these interests call all the shots. At its worst, the state itself actively stamps out such solidarity (which is unconditional and horizontal), while at best promotes charity (which often has conditions and is hierarchical). The state is defined by power itself. And, of course, power protects itself.

"Existing political elites and the ruling classes have a vested interest in keeping things as they are, even if that means the continued murder of Black people by police, foreign military intervention, and a dangerously escalating climate crisis. They will not voluntarily give up power and share the wealth, as has been demonstrated throughout history." - Dana Ward and Paul Messersmith-Glavin

Of course, it is crucial that working class people organise now – in non-hierarchical unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World, and the Solidarity Federation, moving towards workers’ cooperatives, as well as groups like renters unions and radical communal care collectives – embracing an inter-communal, internationalist, and intersectional anti-capitalism that understands and embraces the varying and unique levels of oppression experienced by different communities.

These examples of working class solidarity are, at the time of writing, often quite small organisations in the grand scheme of things – and that’s why information is absolutely crucial in raising awareness of the futility of the current system as well as these alternative ways we can effectively de-legitimise the system, undermine the system and, yes, ultimately replace the system: building the new world in the shell of the old.

"The restricted movement of bodies across borders is parodied by the free flow of cash around the world. The ideas of autonomy and mutual aid can help us rethink our places in the world as interlinked groups who can mutually support one another." - Shuli Branson, Practical Anarchism

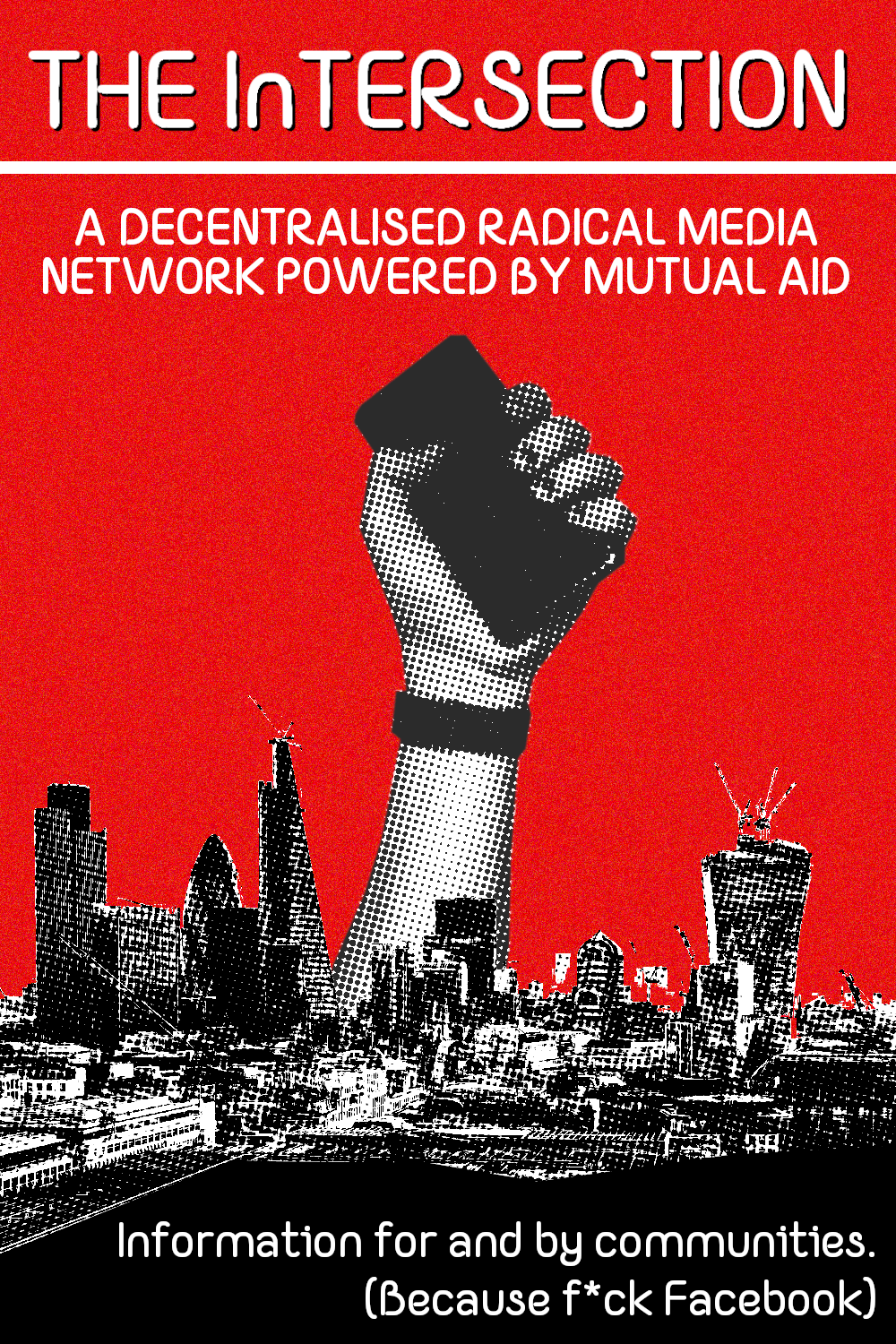

4. Decentralised Networks: Mutual Aid Media

Anarchism is often exemplified by mutual aid – a voluntary, collective exchange of resources and services for common benefit in overcoming socio-economic barriers, and these resources often include food, clothing, medicine, even education and information, prominent in times of crisis like climate collapse and the Covid-19 pandemic, but also meeting the daily needs of communities without relying upon the establishment. Media can, and must, be a part of this. But how?

It may seem like the obvious option might simply be a media workers’ cooperative, and there are examples of these, in the U.K., the U.S., and elsewhere, but they must still compete in the commercial marketplace, and there is not enough protection for horizontal organisations under capitalism. If there’s one thing you can say about capitalism, it’s that it is highly adaptable: the system has ironically co-opted many co-ops to still exist within the capitalist economy (and that famous cooperative The Associated Press even cooperated with the Nazis). In addition, establishment media loves little more than to lure and indeed co-opt clout-chasing voices of “dissent” determined to further their individual careers, leaving the journalists within workers’ cooperatives subjected to the capitalist economy and its corruptible seduction. Journalism, as mentioned, is a class-exclusive profession, largely a landscape for the “brightest and best” who want to get ahead and are therefore compelled to compromise.

"Tearing down the walls between performer and audience, artist and viewer, author and reader, has long been a liberatory goal." - Shuli Branson, Practical Anarchism

There is another way — beyond the reliance upon journalism as a commodity. One where all involved, including the service users, are empowered, with little division between news “reporter” and news “consumer,” and such hierarchy removed completely. Truly mutual aid media: people reporting and consuming information with, by, and for one another as an essential service; the oxygen of organising.

To reflect all of our communities at a grassroots level, then, the ideal media model must largely rely on citizen journalism where information is seen less as what it became mistakenly accepted as (a commodity) and more of what it truly is (a human right).

"In many ways, the definition of “journalist” has now come full circle. When the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution was adopted, “freedom of the press” referred quite literally to the freedom to publish using a printing press, rather than the freedom of organised entities engaged in the publishing business. … It was not until the late nineteenth century that the concept of the “press” metamorphized into a description of individuals and companies engaged in an often-competitive commercial media enterprise." - Prof. Mary-Rose Papandrea

While establishment media reinforced the capitalist status quo and hid behind the excuse of “impartiality” when regularly refusing to critique capitalism’s brutalisation of our communities, citizen journalism has empowered ordinary people in extraordinary ways.

Based on (and named after) the principles of mutual aid, the French-language Reseau Mutu, or Mutu Network, is comprised of over twenty websites dedicated to local radical news, located in various areas of France, in addition to Switzerland, Belgium, and recently expanding its reach even further to help spawn similar sites across Europe.

The Mutu model has succeeded through a transparent editorial process based on set principles that are not just founded on mutual aid but are also anti-establishment, anti-authoritarian, and anti-fascist at their core. While it has grown fast, there are some activists who feel the separate websites repeat more general information and ideas that do not require an entirely different site. Nonetheless, it further demonstrates the potential for citizen journalism, even if not utilising a similar web platform. Numerous other examples exist, offering different approaches to learn from. Cerveaux non Disponibles, also based in France, quickly soared in popularity with the growth of the Yellow Vest movement and have said "the communication of information is really one of the keys of the war." In Latin America, Avispa Midia was inspired by the Zapatistas and state that "media is a terrain of struggle, where we must confront the commercial and hegemonic media."

There are media activists around the world, gathering, collecting, and sharing information, through imagery, interviews, and fearless journalism; speaking truth to power. On demonstrations week in and week out, protesters are filming police to hold them to account in ways their powerful chiefs and their friends in establishment media rarely ever do. But this is not a recent phenomenon. When we reflect on citizen journalism, we have much to be thankful for over the decades, from George Holliday’s incredible documentation of the Rodney King assault, to the mobilisation of entire movements such as Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, and the Arab Spring. Yes, those latter causes heavily relied on the utilisation of social media. But now even that is finally being reclaimed.

Something has emerged as the ideal counter-cultural adversary for Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and the “tech bros”: a federated universe (or “Fediverse”) of decentralised social networks.

“Enter the Fediverse, an alternative, open-source social media network that aligns with anarchist values. Rather than being a thinly-veiled attention and data gathering capitalist vortex, the Fediverse is an actual social network, built out of a multitude of federated, autonomous, and decentralised instances. On the Fediverse, we control the infrastructure, we moderate ourselves, and we can gather and share based on our affinities and desires rather than being guided by addictive algorithms. Many anarchists who have dodged the traps of corporate social media are already here, sharing their projects, art, and ideas.” - from the Fedizine

The Fediverse offers Mastodon as an alternative to Twitter, Pixelfed as an alternative to Instagram, PeerTube as an alternative to YouTube, and so on - but each site all largely able to interconnect and interact with one another to varying degrees, free from corporate walled gardens (or rather, conference suites) that ruined our web in the first place.

Considering the absence of profit motives, ads or algorithms of a cynical nature, you can barely even imagine a more fitting opposition to the walled-off corporate conference suites of Twitter (or “X”), Facebook (or “Meta”), and the like.

“The Fediverse is a collection of decentralised social media services that interconnect via ActivityPub, a specification from the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The Fediverse is nothing short of a renaissance on the social web because, for the first time in well over a decade, social media has a chance to be truly decentralised. This has massive implications for developers; it may be the best open platform opportunity since the blogosphere in the early 2000s.” - Richard MacManus

Indeed, we lost our way. But we can find our way back – armed with the knowledge gained from the mistakes of Indymedia and the hegemony of corporate, centralised social sites. The way in which the Fediverse exists as an entity reflects the vision many of us cite for society in general, with its immense potential for de-commercialised spaces and decentralisation. So appealing are these concepts to humans at our core – and so at odds with the current economic status quo – that the billionaires are attempting to do what capitalists always do:

They're trying to co-opt them.

“Twitter is the closest thing we have to a global consciousness,” said Jack Dorsey as Elon Musk emerged to purchase the service, before continuing: “In principle, I don’t believe anyone should own or run Twitter. It wants to be a public good at a protocol level, not a company. Solving for the problem of it being a company however, Elon is the singular solution I trust. I trust his mission to extend the light of consciousness.” After the sale of Twitter to Musk, Jack helped spearhead the Twitter spin-off Bluesky, aiming to capture those leaving Elon’s Nazi platform with a clone app “cosplaying decentralisation” and lacking the distributed networks of the Fediverse. Is Bluesky a breath of fresh air after Musk seized control of Twitter? Sure, but that's a low standard. Does it remind us of the Twitter of old? Of course, but what will ultimately stop it from suffering the very same fate?

Meanwhile, Zuck’s Meta held meetings with Fediverse administrators, apparently with a view to plug his Threads system into it, provoking a Fediverse Pact of admins pledging to never federate with his poisonous sites. And this federation is part of the beauty of it: while JD Vance joined Bluesky and its users frantically attempted to organise to shut him out with suggestions to, well, ignore him and his fascist followers in the hopes they'd one day go away, Fediverse servers whose code of conduct have rules against fascism would either not approve his registration in the first place, or simply de-federate from any server that did.

"Bluesky sure seems like a lot of fun! They've pulled tens of millions of users over from other systems, and by all accounts, they've all having a great time. The problem is that without federation, all those users are vulnerable to bad decisions by management (perhaps under pressure from the company's investors) or by a change in management (perhaps instigated by investors if the current management refuses to institute extractive measures that are good for the investors but bad for the users). Federation is to social media what fire-exits are to nightclubs: a way for people to escape if the party turns deadly." - Cory Doctorow

But Bluesky's Twitter 2.0 model is apparently more intuitive for ex-Twitter users, and therefore easier to use than Mastodon. The codes of conduct will play a part in this too, even if users don't realise it: the standards are often just plain higher, people push for more inclusive language, and alt text on images is constantly requested (and rightly so). One representative from a workers' rights group actually told me personally that she was reluctant to have a presence for their guild on Mastodon because of such standards. "It was a rather negative experience for me personally - like how it felt was to go from 'The internet is amazing because it's full of amazing people who build amazing things!' to 'Nevermind, the internet sucks, and people are the reason that people can't have nice things' in like the span of 24 hours," she told me. "I love the idea of Mastodon. I want Mastodon to be a thing, and I want to be a part of it being a thing. But my experience has made me afraid that I'm not allowed to be a human being who makes mistakes on there. And boy do I make a lot of mistakes." She clarified: "Basically the primary thing that I feel is not a good match for Mastodon - like not a good match for me trying to take it on myself in addition to all the other things, is I'm not always able to attach alt text to images. Sometimes I forget, sometimes I literally run out of time." She concluded: "My alt-text for stuff is simply copy [and] pasting the words that are on the image into the box...that is all the people on the Big Tech platforms seem to expect from me."

Aside from putting some of her own minor inconveniences above the major inconveniences of, in this case, Disabled people, surely none of us anti-capitalists really think "people" are fundamentally shitty at heart? Isn't that what the capitalist class prefer us to believe? We want to strive to do better, to be better, to be the change we wish to experience in the world. Of course being called out isn't always easy to take, and it isn't always delivered in the gentlest way, for various reasons, and some of us would rather not keep learning (and unlearning) because it's easier to stay in our comfort zone – such as, yes, the "Big Tech" sites.

"Working and living inside hierarchies does not teach us how to deal with conflict. Most of us avoid conflict either by submitting to others' wills and trying to numb out the impact on us, or by trying to dominate others to get our way and being numb to the impact on others. ...Conflict is a normal part of all groups and relationships. But many of us still seem to think that if conflict happens, it means there is something wrong – and then we seek out someone to blame. ...The emergence of conflict does not have to mean that someone is bad or to blame, and the more we can normalise conflict, the more likely we can address it and come through it stronger, rather than burning out and leaving the group or the movement, and/or causing damage to others." - Dean Spade

In fact, I joined a radical communal care collective via Mastodon, and we held regular online meetings and agreed on Dean Spade's book Mutual Aid as a key guide for us going forward, but when the "founder" (and sole admin) of the group had conflict with another member, and was reminded of the book's section on conflict, he suddenly dismissed it because it didn't suit him. Several of us left and while his group later collapsed "because people" (his words), ours has continued to this day – yes, with living breathing people as part of it, partly lasting so long because we learned from such guides and experiences, while it seems he, sadly, did not. It's hard to unlearn hierarchy when we're brought up with it in our lives. But suggesting people – human beings – are innately shitty seems like a cop-out too many use to justify doing shitty things. And it's straight from the capitalist hymn sheet. It's what capitalists prefer us to believe and say because it justifies their system of hierarchy and exploitation.

"Do you believe that human beings are fundamentally corrupt and evil, or that certain sorts of people (women, people of colour, ordinary folk who are not rich or highly educated) are inferior specimens, destined to be ruled by their betters? If you answered 'yes', then, well, it looks like you aren’t an anarchist after all. But if you answered 'no', then chances are you already subscribe to 90% of anarchist principles, and, likely as not, are living your life largely in accord with them." - David Graeber

For now, Mastodon will likely continue to be perceived as lesser to Bluesky until the inevitable "enshittification" occurs, at which point more people will (perhaps finally) realise that Mastodon, and the Fediverse as a whole, reflects the world we want, and it's one worth fighting for (yes, even if that includes a little conflict with those of us on the same side along the way).

Fundamentally, private entities are desperately attempting to retain their dominance on the social media landscape. Beyond the billionaires’ ideological motivation to essentially influence public discourse, there is also the obvious base incentive for them, as capitalist endeavours, to sustain their services in order to meet their business aims. While they may enjoy the narrative that us Fediverse users are a small minority on the fringes of a social media world where their sites are still “the places to be,” their recent actions only betray their concerns that there are, instead, more and more people attracted to the core principles of the Fediverse.

Those old social media sites aren’t just facing an existential crisis; they were flawed creations to begin with, built on sand – as mentioned, they were never perfect.

The Fediverse isn’t perfect, either, although it is structured on stronger foundations from the start – foundations compatible with anarchist principles. And as anarchists, we realise that perfectionism is the enemy of good. But we can still try to do better, even in the face of adversity.

For starters, servers cost money, and instances of the Fediverse face a scarcity of resources that the likes of Elon and Zuck don’t have to worry about so much. There are other challenges too. Yes, servers must become more transparent, accountable, and democratic, but that will require more rights alongside more responsibilities for users, if they are so willing. Yes, Nazi punks can set up their own vile servers, but the rest of us will simply de-federate from them, setting them adrift alone; ostracised, as they deserve to be. And yes, even servers with codes of conduct that promote safe spaces for marginalised people have their own problems with ignorance, or lack of understanding of privilege and power imbalances, but unlike X and Meta and sites like them, such instances are often experiencing critical yet constructive, diplomatic discussions about how to improve the form and content of the servers in question, which cannot exist in the first place in centralised, corporate social media – because X and Meta are, inherently, incompatible with democracy. This is why the Fediverse is important to value, nurture, and improve. As difficult as it can be in this time of crisis, we must remember to learn the lessons of Indymedia.

Challenges also arise when speaking about the Fediverse as one entity, when in fact it is, by its very definition, comprised of many different networks like Mastodon, Pixelfed, PeerTube, Castopod, Lemmy, and more, each with different form and content, offering publishing opportunities for text, images, video, music, you name it. These remain crucial tools for a much-needed multi-media citizen journalism at the grass-roots level. But not all software is the same, and this requires consideration.

What was described as a Twitter ”exodus” when Elon Musk took over the service saw swathes of users switching to Mastodon on a matter of principle: they may have wanted a social network that functioned similarly to what they were familiar with on Twitter, but without the corporate ownership and increasingly fascistic culture. Meanwhile, the Reddit boycott was arguably more about Reddit charging third-party developers for commercial access to its application programming interface (or API). Thus, the culture on Reddit alternatives such as Lemmy may be more comparable to Reddit itself, than most Mastodon servers can be compared with Twitter.

"The medium is the message." - Marshall McLuhan

If, like Reddit, a site has an “up-vote” and “down-vote” system on its posts, the discourse is inevitably influenced through that consideration by the user, which is not always useful. The exception is the Beehaw instance, which took away down-votes entirely and indefinitely in an attempt to nurture a kinder culture, based on the logical assumption that if a post brings little to the conversation, it will simply lack up-votes, negating any need for a down-vote feature that can be – and often is – abused on Lemmy, just as it is on Reddit.

Activists have long called on social movements to campaign “wherever people are” but, morally, that can no longer include the social networks of late capitalism’s billionaires, be it the proverbial Nazi bar of Elon’s X, the misinformation hive that is Zuck’s Meta, Trump's “Big Tech” enablers, or the next big “tech bro” offering. The Fediverse is ours to utilise, and create. By its very definition, it is collectivism over individualism. By its very structure, it can be order without power. This is why we can utilise the Fediverse to develop our radical media networks - building the new world in the shell of the old; seizing the means of social media.

Forget closed-off Facebook groups and X accounts. Forget about wondering where to find information on the latest meetings, campaigns, demonstrations and resources of interest to anti-capitalists and anti-fascists. With a Fediverse radical media network based on something similar to Beehaw's form and inspired by Mutu's content, we can build a framework to find and disseminate such details – town by town, region by region. Wherever we are that day; getting involved, learning and sharing and changing our communities for the better. Rejecting disinformation and helping people to better understand the principles of mutual aid, tackling the challenges we face, together. Intersectionality at its core.

I for one plan to do my best to help build this Intersection. If you'd like to, as well, email me. And let's keep communicating via the Fediverse!