The 21st century began, in many ways, in fitting fashion: as a harbinger of things to come. The fear and panic around the Y2K bug produced vast amounts of confusion and conspiracy theories that would come to pollute our online spaces with increasing frequency.

And yet it had started out so promising: with the web offering an unprecedented method of sharing information and ideas that had lacked coverage in the pages of newspapers and the bulletins of television news. Initially, this was often found in the weblogs (or "blogs") that provided a platform for voices rarely heard up to this point. “The web dramatically alters the balance between multinational and activist media,” declared an opening statement of the first Independent Media (or Indymedia) Center. “With just a bit of coding and some cheap equipment, we can set up a live automated website that rivals the corporates’.”

Under the slogan “Don’t hate the media – become the media,” a network of Indymedia Centers spawned out of the WTO protests in 1999 and quickly expanded world-wide with the aforementioned global opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, as media activists reported on actions in mere minutes, complete with photos and videos, often offering different perspectives on protests against the G8 and the G20 to those narratives provided in the papers or on TV.

My role as documentarian through my non-profit SilenceBreaker Films merged with that as an early contributor to Indymedia, reporting from protests and pickets, sit-ins and squats. On my travels researching examples of what seemed effective media activism, I visited infoshops from GlobalAware in Toronto to Adbusters in Vancouver, and made connections in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in particular. While still trying to keep funding coming in and hiring friends at SilenceBreaker Films back in Britain, I stayed in the GTA for months at a time – taking part in union drives, demonstrations, direct actions, and occupations, and made speeches at rallies and radical events in ways which were probably not smart for someone on temporary visas, sporadically staying in a housing co-operative with a volatile Canadian who at least shared my passion for communication studies, pursuing the subject at Wilfrid Laurier University, whose students urged me onto the board of Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group (LSPIRG), despite (or because of) the fact I was British and not a Canadian citizen.

It was at Laurier I was asked to give a speech for a journalism conference, where I met filmmaker Tim Knight, who stayed in contact with me for years until shortly before his death and – when I asked him about the emergence of citizen journalism – cited his fellow Torontonian, the 60 Minutes correspondent Morley Safer: “I would trust a citizen journalist as much as I would trust a citizen surgeon.” I made the counterpoint that if the modern equivalent of journalism was healthcare where the doctors were killing people instead of saving them, then you’d take your chances with someone else having a go at it – and that's where we're at, because journalists like Tim Knight rightly warned us against vested interests controlling healthcare with no irony, despite working in an industry of news media almost entirely controlled by the capitalist class.

"'The police told us to stay away,' 'The police told us to turn off the cameras.' These days, 'real' journalists often do what they're told. Good thing you're not a 'real' journalist... You deserve better. We all do." – Ales Kot

We do deserve better. But what? And how? Certainly neither example of my own media activism would prove to be an effective option.

Media fail

Back in Britain, a colleague and friend I had trusted set about seizing the narrative – and a whole lot more – in my absence (I'd learn much later that this friend had form). As a result of this individual's influence, I was erased from our own shared history as founding directors of a community organisation called ROAR, and SilenceBreaker Films was shut down completely, with its thousands of pounds of assets allegedly transferred over to my former friend and/or those who aided and abetted the coup. The lesson here is that this was all only possible because for SilenceBreaker Films to even access grants in the first place, it had a hierarchy: a committee in place above me, one that in my absence was influenced by my former friend, who helped ensure that the organisation’s closure was also blamed solely, squarely, and entirely on myself in my absence (even to funding bodies who subsequently blackballed me); the committee exercising their rights, without responsibility.

Meanwhile, with no such ruling body, Indymedia was experiencing a challenge at the other end of the spectrum: this global network’s non-hierarchical structure was both its strength and its greatest vulnerability.

"As the anti-globalisation movement from which it had emerged started to ebb away...Indymedia went into free fall. The open publishing nature which had allowed anybody to take part, write up action reports and publicise events, proved also to be its weakness as conspiracy theorists and anti-Semites began posting whatever they liked. It was partly in reaction to these drawbacks that we launched what eventually became libcom.org." - libcom.org

The rise of social media

In addition to Indymedia’s lack of a coherent, comprehensive system of democratic editorial oversight, the "blogosphere" was at the same time being somewhat superseded by the emergence of social media sites that co-opted such features of content creation and media uploads alongside messaging and profile-building.

"Social media eventually smothered the blogosphere. I remember this time well. The harbinger of it was when blog comments dropped off. You see, the comments of blogs were really the first social networks. Every blog had 'regulars' – people who followed a blog and commented a lot. ...But then, seemingly overnight, people stopped commenting. Well, they did comment, but they just did it over on Twitter. ...Twitter became the biggest driver of traffic. I think this had something to do with a tie to identity. Comments on blogs were mostly unauthenticated – you were only identified by what you typed into the 'name' and 'email' boxes, and there was no way to verify that. But on Twitter, commenters effectively became publishers. Their comments were part of their social media account, and they were building their own audiences in that sense." - Deane Barker

Yes, profiles were increased in every way: taking advantage of the loss of faith in establishment media, commentators catapulted careers from these "platforms" – clout-chasers like Owen Jones and Aaron Bastani connecting with me online until they gained greater status and opportunities, caring so much about popularity and their online “followings” that they remained on such sites long after fascist takeovers. They weren't the only ones, either. Under the guise of offering “alternative” media, a wave of websites overwhelmed us within just a few years, leaving us with a disorientating flood of sites such as The Young Turks, MintPress News, Redfish, and The Grayzone building a reputation for fiercely “anti-imperialist” reporting – only for such coverage to be largely restricted to critiques of Western imperialism, with funds from Russian powers supporting these narratives that undermine Western superiority while platforming white supremacists and far-right conspiracy theorists.

The existence of anything questioning Western imperialism, at face value, can seem appealing to many of us, and these outlets are often designed to exploit such sentiments while being at best big state socialists, or at worst disinformation channels serving the interests of the powerful Russian government, often platforming bigots and pseudoscience personalities. But across the web, they’re all fighting for clicks, whether they be Bellingcat exposing The Grayzone as state stooges, or The Grayzone attempting to return fire by making the same claim back at them. Regardless of the influences or agendas, they’re all compromised and open to these criticisms (though some worse than others, of course). And, in order to raise and retain their profile, they’ve all been largely dependent upon traffic from pages on social media sites.

While MySpace’s purchase by Rupert Murdoch was ill-fated, it was not because social media was contracting in any way, but because it was in fact expanding: as the emerging sites suddenly rivalling MySpace attracted users in droves, what remained of the Indymedia network began to largely collapse. Facebook and Twitter were utilised for both the Arab Spring, and then the Occupy movement, which rose up after the 2008 global financial crisis (as mentioned, large banks were bailed out; large swathes of populations were subjected to harsh austerity measures). The system remained in place – essentially, it turned out, aided and abetted by the same social media powers that were supposedly useful in challenging that system.

The development of the world wide web stoked our naive expectations of a more free exchange of ideas in an online commons that was, under capitalism, quickly seized and bought up by virtual landowners. But few phenomena offer a better example of this than social media centralised, owned, and controlled by corporations.

As new media replaced old media for advertising opportunities, companies were wooed by promises of a budding target market, one all too willing to engage with brands. It became a largely accepted model: online spaces with millions – even billions – of users, all providing their data. In turn, this was sold to advertisers, creating huge profits for private social media companies. User data provided a wealth of information through profiles, polls and social graphs. Tools emerged to gauge favourite foods and films, or places a person frequented – even private matters such as sexuality and personal anxieties became figures in datasets.

Misinformation

Far from being platforms in proverbial “town squares”, as they were often lovingly referred to, these social media sites – aside from making money from selling user data to advertisers – are privately-controlled entities subjected to the whims of billionaire owners and their desire to protect the capitalist class, including by enabling the spread of misinformation.

In the run-up to the U.K. general election in 2019, a staggering 88% of Conservative Party posts on Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook were “misleading.” (Facebook did ban one of their ads, but only because it infringed the BBC’s intellectual property rights); they went on to win that election. More recently, Covid denialism (linked heavily to the far right and nicely serving capitalist ideology) has been permitted to thrive via conspiracy theories thrown around on Facebook as well, as the “left” utterly failed to effectively emphasise the importance of ongoing mutual aid and Covid-safe workplaces, instead following along with state policy of capitalism over care; commentators and clout-chasing leftists falling over one another to race back to “normality” in an ongoing pandemic – a mass disabling event. Subsequently, conspiracy theories and right-wing authoritarians promising order increased their appeal, and were able to further their ideology of ableism and eugenics.

"The conspiracy mindset does point symptomatically to the fact that many people feel that the world is totally wrong; that our lives are lived in a way that doesn’t actually make sense and serves almost no one." - Shuli Branson, Practical Anarchism

Yes, conspiracy theories, misinformation and misleading campaigns thrived more than ever before. Even very mild social democratic challenges to “business as usual” such as Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn were soon stamped out.

“Politics hates a vacuum. If it isn’t filled with hope, someone will fill it with fear.” - Naomi Klein

In countries from the U.K. and U.S. to Russia, the prevention, decimation, and eventual disappearance of even these wildly popular yet remarkably mild alternatives and tweaks to the system led populations of angry, confused, voters remaining an electorate to become seduced by something else, something different, that promised them a much-wanted drastic shake-up: a form of fascism openly promoted, for years, by a media that meanwhile engaged in an all-out assault on all things not conservative or neoliberal. This fully unleashed plague of fascism grew and spread to Brazil, Argentina, Italy, the Netherlands, and all around the world. Nowhere has been safe from these toxic elements of capitalism’s cocktail of authoritarianism utilised in an attempt to justify its principles of power, profits, and endless exploitation and extraction of planetary resources as we approach the brink of destruction. People are faced with not just worldwide inequality, but also an ongoing global pandemic and climate crisis. All the while, the capitalist system remains supposedly sacrosanct.

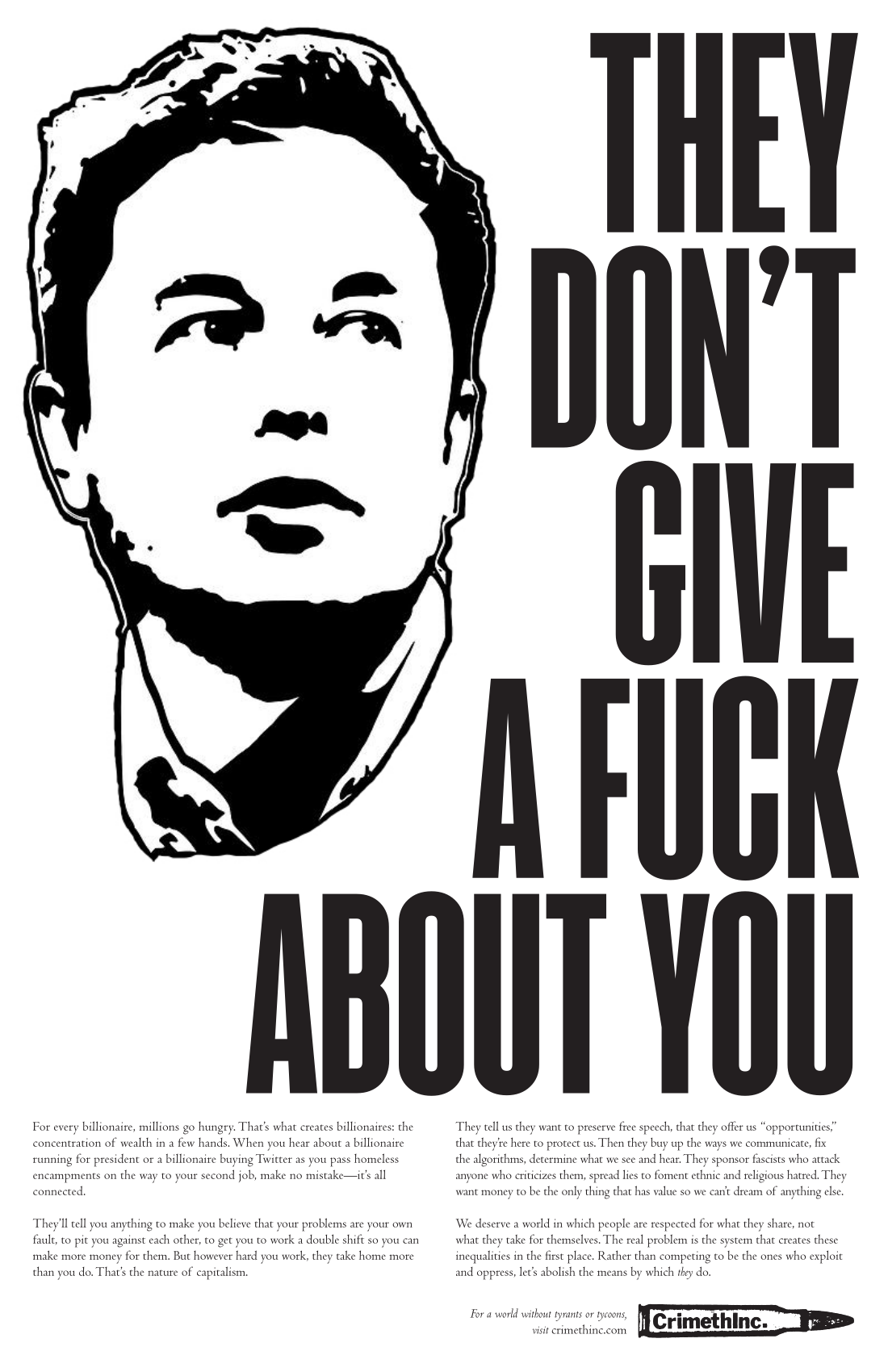

Then came Elon Musk. Twitter was far from perfect even before he bought it – founded by Noah Glass, Evan Williams, and Biz Stone, with Jack Dorsey as CEO, it was designed to be a private entity which inevitably turned its attention towards generating revenue. When Musk purchased the service, he claimed to be a “free speech absolutist” at the same time as overseeing bans on anti-fascist accounts such as Crimethinc at the behest of the far-right voices he adheres to and even amplifies online. With capitalism accelerating global crises, and many now rejecting traditional electoral systems as realistic solutions, Crimethinc is one of several similar accounts that obviously threaten billionaires such as Musk – personally, politically, and practically: they make him feel threatened because they are anarchistic. And not because anarchism is, in fact, something sinister. Not for us, it turns out, anyway.

“Chances are you have already heard something about who anarchists are and what they are supposed to believe. Chances are almost everything you have heard is nonsense. Many people seem to think that anarchists are proponents of violence, chaos, and destruction, that they are against all forms of order and organisation, or that they are crazed nihilists who just want to blow everything up. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Anarchists are simply people who believe human beings are capable of behaving in a reasonable fashion without having to be forced to. It is really a very simple notion. But it’s one that the rich and powerful have always found extremely dangerous.” – David Graeber