On numerous occasions – on this very site – I've written about how I became active online around the launch of Indymedia and the "blogosphere" after getting my first post-Commodore 64 computer connected to the internet just as the "millennium bug" conspiracy theories spread, a disease of misinformation that would grow to infect many of those online spaces I loved, and eventually be promoted by their supposed successor, the "Web 2.0" of Facebook and Twitter (and we know how all that turned out).

But back in those early days, I was largely as ignorant as anyone else. While my student loan had paid for my home computer set-up, I was a media degree dropout by the time I was on a welfare-to-work programme for a local council, where workers would frequently exchange emails to set up meetings with those from other departments – yes, people they had previously never met in-person. Because work is held up so high in our capitalist culture, no stigma came with such meetups, while there was a great deal of stigma attached to meets from outside our working lives – in fact, it was a source of ridicule for those meeting friends or romantic interests they had connected with via online forums or the early dating sites that had merely replaced the local lonely-hearts ads. Today, much of these quaint attitudes seem laughable, yes, but at the time I, too, was caught up in a lot of it, and I can offer an example.

Unreal

While on my media degree in 1999, I had been on a university trip to Paris, where I met a group of Canadian students. Accepting a subsequent invite, I arranged a visit to Ontario after some of them stayed in touch with me via email, which was of course perfectly acceptable because we had already met in-person. What was likely less acceptable was the fact that – when I wasn't playing Unreal Tournament – I had been chatting at length with an Ohio native via AOL Online chat rooms, over the course of several months, and we got along very well – even feeling a closeness and affection for each other – and by pure coincidence were both, at the exact same time, going to be with our respective friends in Ontario (which isn't that far from Ohio, by North American standards). Despite the fact we had even spoken on the phone, apparently it wasn't "in real life" because we had yet to physically meet in-person, and buying into such narratives, I broke this person's heart when I began seeing other people as our Toronto rendezvous approached. Fortunately, through the turn of the millennium, it seemed we were able to move past all that after a meeting which, as it so happened, merely confirmed everything we had thought and felt and anticipated from chatting online, on the phone, sharing photos, and exchanging snail-mail. Yes, despite all that evidence, I couldn't accept the obvious, because I had allowed myself to be convinced that nothing was "real" until meeting in-person. Yet it turned out it was all quite real indeed. All too real. And all too painful sometimes, too. (Sadly, I would even go on to repeat this mistake, unintentionally causing heartbreak because I dismissed even my own feelings as "unreal" in the absence of an in-person meeting, something I'm not proud to admit.)

Although still early in my media activism, chat rooms were gradually holding less appeal for me as the Indymedia network expanded and my city of Sheffield had its own site I would begin to contribute to. The terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, had taken place just days away from my impromptu departure from Ohio – via Pennsylvania and New York – forced by the collapse of my relationship with the (somewhat understandably) insecure American, who joined in with other Americans in calling for vengeance, violence, bloodshed and war in response to the 9/11 attacks, while I headed in a different direction of anti-war activism, reporting on protests as they increased momentum and connected to anti-racism and anti-capitalist movements I became engaged with.

Around the same time, we had the scandal of Enron, a corporation whose profits – it became apparent – were not in fact at all even remotely "real," and as I write this now I realise Enron filed for bankruptcy on this very day in 2001. Of course, that was followed just a few years later by a global financial crisis caused by financial packages that also weren't "real," prompting governments that previously had no "real" money to spare for, say, social programmes, to suddenly print money to bail out banks – and voila: "unreal" money was suddenly made "real." Despite demonstrations of "the 99%", we were still expected to listen to our bosses in the workplace to tell us what was "real" and what was "fake." No wonder setting up a meeting with Sharon from accounts via email seemed like serious business, but finding friendship or love or anything else more meaningful on some website was, apparently, laughable.

"Is any of it real? I mean, look at this, look at it! A world built on fantasy! Synthetic emotions in the form of pills! Psychological warfare in the form of advertising! Mind altering chemicals in the form of food! Brainwashing seminars in the form of media! Controlled isolated bubbles in the form of social networks. Real? You want to talk about reality? We haven't lived in anything remotely close to it since the turn of the century! We turned it off, took out the batteries, snacked on a bag of GMOs, while we tossed the remnants into the ever expanding dumpster of the human condition. We live in branded houses, trademarked by corporations, built on bipolar numbers, jumping up and down on digital displays, hypnotizing us into the biggest slumber mankind has ever seen. You'd have to dig pretty deep, kiddo, before you can find anything real. We live in a kingdom of bullshit, that even you have lived in for far too long. So don't tell me about not being real: I'm no less real than the fucking beef patty in your Big Mac." - from the TV show Mr. Robot

Covid-19

Then the pandemic hit, and the bosses were soon again telling us what was "real" and what was "fake." That well-known (but by no means best) video conferencing programme, Zoom, exploded in use as people were trying to stay safe in the midst of a mass disabling event, working from home. Likely shaking with their addiction to profits, capitalists and their spokespeople in government were soon again setting for us the definitions of what was "real" and what was "fake": mere months into the pandemic, politicians were telling us to get back into restaurants to share air and gobble up grub so the profits could keep being gobbled up by the rich – and with no irony, even Zoom's bosses were ordering their own workers to get back into the workplace to dismiss the actually very legitimate threats to our health. A few years in, the World Health Organization (WHO) was able to appease the acolytes of global capitalism by stating that the Covid-19 pandemic was no longer a "Public Health Emergency of International Concern," which characterises the initial phase of a pandemic. However, contrary to popular belief, the WHO did not declare the pandemic itself over – only arrogant politicians did that. As Covid continues to disable people on a frightening scale, governments still downplay it for the sake of their global economic system, whether by dropping it from agendas, discouraging mask wearing, winding down vaccination drives for the broad population, gaslighting patients, or removing social security, targeting Disabled people. And the ableism sadly doesn't end there.

Right from the start of the pandemic, we were told once again that work makes us free, that work is real, unlike the fake stuff we were suddenly engaging in, like bread-baking and mutual aid – you know, the world we want and that is within reach, were it not for these systems of distraction and oppression. And the trade union movement missed a defining opportunity – rather than helping us dispel these illusions, too many careerists and clout-chasers on the union scene were unable or unwilling to recognise and fight for a world beyond work (I often mention how I remember the Trades Union Congress, right as Covid hit, ignorantly tweeting "JOBS JOBS JOBS JOBS...") The very least they could have done in accordance with their principles was fight for Covid-safer workplaces (which some unions have).

While, as acting secretary, I was helping to revitalise my local branch of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), many of its members were dismissive of Covid precautions and some of its "anarchists" were waiting for the government "roadmap" to make sense so they could dutifully adhere to it; meanwhile I explored the launching of a "Local" of the Solidarity Federation in Sheffield with a few other anarchists who ignorantly suggested meeting in a pub and when I told them that, in the ongoing pandemic, I was still taking precautions – not least while caring for my partner (disabled by Covid), who was also interested in being a member – I was told their focus was instead "a real physical presence" and "to establish an anarchist community of people as much as possible," which we can only assume, then, would be excluding Disabled people like my partner, as everyone was being told to "go touch grass."

"When we denigrate online spaces and say they can’t be opportunities for community-building, we are actively excluding some of the most marginalised people in our society," wrote author and librarian Lachrista Greco. "It’s no wonder that disabled people continue to be forgotten about or pushed aside throughout the pandemic (which is still very much ongoing). People who are home-bound, bed-bound, or just can’t make it to in-person meetings/hangouts/etc need and deserve community. Who is anyone to say that online spaces cannot exist as community building?"

Lachrista continued: "Why do we act as though the internet is not IRL (in real life)? I personally do not separate my online life from my offline life. I am the same person online as I am offline. I know some people need this separation for safety reasons. However, what I need people to understand is that 'IRL' is both online and off. Online life is not fake or less-than. When we talk like it is, we do an incredible disservice to those whose lives might look vastly different from ours. We do an incredible disservice to online communities that include very real people. This isn’t the internet of the 90s." Greco is right – it really isn't. We've learned so much more by now. We know that there's no default distinction of "in real life" and "fake," only our individual choices to share what we feel comfortable to – just the same as we would while talking with a neighbour outside; we're hardly going to give them our credit card number, but we'll probably choose to share some information, such as our name, so that we can feel we have a more personal exchange with them.

Governments have, of course, been faking concern for the "safety" of citizens by clamping down on internet freedoms. While most abuse happens in the home, these politicians aren't calling for glass walls in houses – instead, again and again, they're pushing for more and more surveillance of their citizens online, sometimes introducing impossible requirements that further push people onto centralised sites controlled by right-wing billionaires. I guess we should have seen it coming: as the internet enabled people to exchange their own media and contributed to social movements from the WTO protests to Occupy and the Arab Spring, it was only a matter of time until the authoritarianism of Late Capitalism turned its attention to the web.

Online Matters

As a graduate of the School for Social Entrepreneurs, in 2010 I founded my own non-profit called SilenceBreaker Media that engaged people in disadvantaged communities to get online using reconditioned computers (usually installed with Linux) so they could create and share their own media, vocalising issues important to them. To better achieve this, we eventually ended up largely working with local libraries as something known as the FreeTech Project, (branching off separately from SilenceBreaker Media, under the umbrella of Libre Digital, which I had hoped would become an over-arching worker cooperative).

Given that, at age 11, I was pulled from an abusive school environment by my mother who taught me at home, it's probably no surprise that rather than "teach," I instead facilitated the tech workshops, borrowing from the "action learning" I'd experienced at the School for Social Entrepreneurs, and encouraged skill-sharing. People praised the informal, friendly approach to tech workshops, where we rejected a one-size-fits-all method and helped people save time, money, and waste by breathing new life into their old devices installed with free and open source software they actually found to be less complicated, to boot.

In many cases, the FreeTech Project became the de facto tech support for people in those communities, and we had plans to develop "tech banks" as part of an entire network of libraries that would be able to gain, retain, and share skills and tools to sustain such "tech support" groups in their communities long-term. But before we could do that, Covid hit – something we were completely unprepared for (and our Codes of Conduct and Health and Safety policies took time to catch up with). The few groups we had contact with at that time were given the chance to join us via online workshops, but many individuals didn't have the skills and/or confidence to do so. Nonetheless, as we moved to more collaborative ways of working with a view to becoming a worker cooperative, we have been able to continue delivering online workshops for the last five years, building on the previous ten years. That's an achievement. But that doesn't mean there weren't challenges – and two in particular come to mind.

Firstly, we weren't able to attract as many Covid-cautious people to online workshops as we'd have liked, meaning many attendees were contacts from the old days and/or seduced by the dominant culture – one away from libraries and "libre" principles, and instead the buy-in to Big Tech and "in-person" events. Big Tech browbeats the marginalised with mass advertising and normalisation of their products via their deals with local government and other workplaces – all forces tough to challenge. In addition, despite the fleeting days of 2020 where people claimed "this will change everything" and we'd learned lessons around wasting time, energy, and resources, that overwhelming consumer culture also encouraged ableist approaches towards learning environments, with people soon back to assuming "IRL" is the only effective way. "When I see the push to return to in-person everything, I question whether people learned anything from this pandemic," Lachrista Greco also stated. "So much was moved to virtual initially, only for it to be taken away the second abled people were 'done' caring (if they ever cared to begin with). If we are truly committed to inclusion (which, I’m not sure many abled people are), then why aren’t we listening to disabled people? Why are we saying that community-building can only happen in-person?"

Secondly, part of the reason we weren't able to more effectively reach more Covid-cautious folks was because Covid-aware voices were in the minority within our organisation as a whole. We also realised that converting to a worker cooperative wouldn't change that. Nor would it change the fact that I was just one voice from the organisation on the workshops that was trying to dispel the "IRL" rhetoric by emphasising that what we do online matters – including the choices we make: we don't have to support Big Tech that literally causes harm to marginalised communities through destructive data centres, genocidal products, and blatant support for fascism. Boycotts work. And they're even easier when there are alternatives to that Big Tech.

Nonetheless, this is sadly where a lot of tech dialogue fails us.

"Before WWII, the city of Amsterdam figured it was nice to keep records of as much information as possible. They figured the more you know about your citizens, the better you’ll be able to help them, and the citizens agreed," wrote Dutch tech entrepreneur Boris Veldhuijzen van Zanten. "Then the Nazis came in looking for Jewish people, gay people, and anyone they didn’t like, and said 'Hey, that's convenient, you have records on everything!' They used these records to very efficiently pick up and kill a lot of people." He continued: "After the war, The Netherlands, and Amsterdam, in particular, became a big proponent of giving their citizens privacy, and we can all understand why. So, when a service wants to know everything about you, to help you better, their intentions might be super valid, and your trust in them might be defendable, but we don’t know what the future brings. We don’t know what future governments will do."

This resonates as the UK's Labour government – that of Blairite ID cards – is now laying the groundwork for its successors, which could very realistically be the openly fascist Reform party. Over in the United States, Trump's assault on marginalised people is in full effect, and the Big Tech that backed him have aided and abetted it. So even if you're privileged enough not to feel vulnerable using Big Tech, it's worth using the conscience we have and supporting the better alternatives that exist. And we must leave no one behind. After all, none are free until all are free, right?

While there has been a great increase of advocacy for online privacy and security in the face of bad actors from states, corporations, and individuals, too often these articles and websites fail to connect them with human rights and ethics, even when taking sustainability into account. For example, an article that rejects Google will then in almost the same breath endorse Brave, which is run by Brendan Eich, who was ousted from Mozilla for his anti-LGBTQ+ bigotry. There will be uncritical praise for Proton, Kagi, and even Framework. When that's the case, we're really admitting that we don't care about the privacy and security of more marginalised people, only our own individual privacy and security (which is essentially as practicable as attempting to only breathe our own air in a room full of people during a pandemic). Like many of you, I don't want to live in that world, and yet we only have this one – so we have to change it. And we can. By rejecting Microsoft Windows, Apple Mac and iOS, Googled Android phones, Elon Musk's Nazi platform of X, Meta's Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, and the con of so-called "AI," to name just a few of the products that aren't just bad morally, but just plain bad; so terribly inferior in many ways.

On my previous workshops, it's been tough to reconcile facilitating, even enabling, people using these inherently bad products; constantly helping them solve another problem that will inevitably be followed by yet another problem soon after because, fundamentally, the problem is the product itself. For example, it's difficult to keep your programmes up-to-date because there's no software centre with your operating system; if there is an app centre, it's bombarding you with advertising. But everyone assumes paying an extortionate amount of money for something like Microsoft Windows or Microsoft Office means it must be a more valuable product when, in fact, it's largely worthless. And much of it would have met the definition of "malware" not too many years ago. Now people pay to be infected with this stuff. My lovely old colleague recently suggested alternatives might mean a steep learning curve for our workshop participants. But how is using this preexisting tech trash not presenting a steep learning curve? People seem constantly baffled and stressed out using it, and we could never be socially sustainable if people just keep coming back to us confused.

I'm tired of witnessing folks struggling with their device because it's one full of baked-in crud like "AI" and ads, while being completely ignorant of the "AI"-free, ad-free, hassle-free alternatives like Libre Office, Signal messenger, the Fediverse decentralised democratic social network, the Fairphone, de-Googled Android phones with a straight-up app centre similar to those offered by the plethora of Linux distributions, many of which – since working in this area – I've used over the years, never once looking back, except to see how far I've come from the days of being sickeningly ripped off. I've used Fedora (from Red Hat, now owned by IBM and paying the price for it, in many ways) to Mint and Manjaro to, yes, Arch Linux, and more recently Pop!_OS, to name a few.

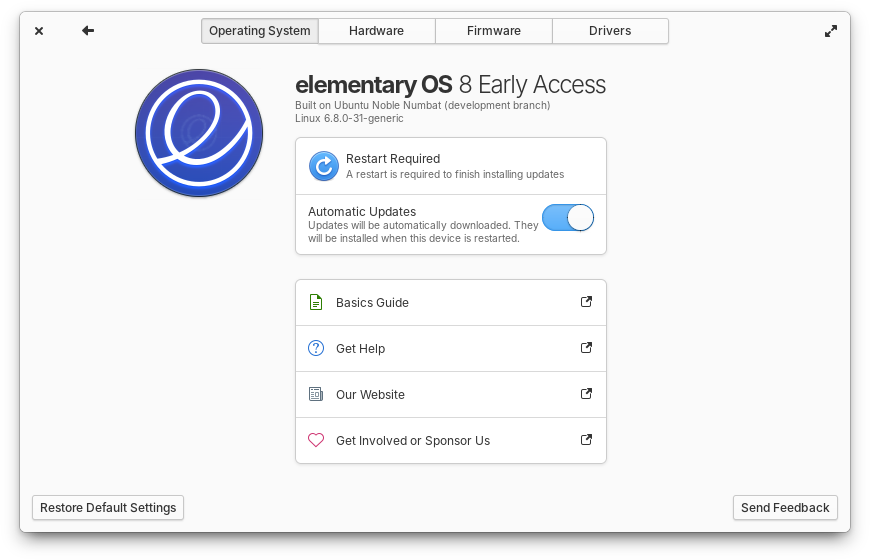

Then there's elementary OS, which I've been interested in for a while, but won me over when its founder, a rather brilliant trans woman named Danielle Foré, publicly stated: "I happen to own a little open source software company that is expressly anti-fascist, has a 'No AI' policy, and has recently been called 'aggressively queer' in case you’re interested in supporting tech companies like that." Rather than pushing some "such personal opinions do not reflect us" angle, the official Mastodon account of elementary OS itself followed up by reinforcing: "We’re a queer woman owned business and we believe in equality and inclusivity for all our LGBTQIA+ siblings... We don’t use AI to make our software... We condemn fascism, white supremacy, and other harmful and oppressive ideologies. And we enforce an inclusive Code of Conduct in our communities."

What's more, Danielle Foré recently declared "supporting disability is our social responsibility," while introducing accessibility improvements that Linux has long been perceived to lag behind on.

This matters. It's what I want to support. It's what gave me the very last little nudge I needed to complete a full installation of elementary OS on my desktop computer that I'm aiming to carry out in the next few days. And despite all the confirmation bias behind some of the online criticism of this (actually incredibly beautiful and smooth) operating system – much of it filled with transphobia – I've found it to be, well, elementary (pardon the pun). And since it's "pay-as-you-feel," I plan to donate what I can currently afford, and contribute further in the future (and purchase their merchandise too). I want to support them, and I want to promote them.

Erase and Reformat

Staying up-to-date of tech changes means – for me – also keeping abreast of the mergers, the acquisitions, the changes in policy and culture, and the power we possess to withdraw our custom as we wish. In many workshops, I found people frequently confused "free" and "open source," almost assuming they were one and the same; interchangeable. As we know, we're usually talking about "free" as in "freedom," not "free" as in "free food." Contrary to what people might think, I'm very happy to pay for good products – just not with my data. And there's the rub: for all the longtime dismissal of tech use as not "IRL," people have let it give them a tolerance to abuse they would never tolerate "IRL."

Think about the old days, when the phone was still considered more "IRL" than online interactions. "If the phone companies were recording the words we use in our conversations to sell our preferences to advertisers and make machine learning-driven inferences about us as humans, we’d lose our collective minds," pointed out one Mastodon user named Jaz. "But when Internet companies do it we've managed to create a world where that's … normal … most people don't like it but believe there's no alternative."

Yet there are many alternatives. And that's what I want to now utilise my skills and experience from the past twenty-five years towards: developing a not-for-profit, part-time, "small tech" worker cooperative in England to raise funds so we can discuss and highlight technology at the intersection of sustainability, security, privacy, and ethics, hosting online (and possibly Covid-safer in-person) workshops as well as webinars and consultation for individuals, groups, campaigners, and the marginalised – and share resources on how we can use tech better. I hadn't even finished writing this when, this morning, I was hired by an LGBTQ+ Disabled social enterprise for consultation on just this kind of thing. The demand is there. But I don't want to do this alone.

So, I'm calling it "The People's Tech" – not just because I want it to be democratically controlled by its workers and even members, but because the people and not governments and corporations should have control over their own tech.

It turned out that our online spaces were no less part of "IRL"...and no less vulnerable to the forces of Late Capitalism. It's time we finally took it seriously – and stepped up to the challenge at the intersection of privacy, security, sustainability and inclusivity.